Dressing in my Generation.

By Ogiri John Ogiri

My society,my generation, was known for decency in dressing. I grew up in a generation and a time when clothes were worn to cover nakedness and for aesthetics in order to command respect. In my generation, women were not ashamed of wearing wrappers. They wore a locally-made fabric called "opatali". In fact, they wore it with pride.They did not bother themselves or fret about hand bags or purse as each had what was called " Inyonko" a hand-made local purse in which they kept their money and some other portable valuables. It was usually tied around their waists as they went about their daily farming and trading activities. Many of them equally had local boxes made of metal or aluminum materials. In those boxes they kept their clothes bought for special occasions like burials, marriage ceremonies, visits to family members, festivals (Ej'alekwu festival and the New yam festival also known in my local parlance as "Achomudujé" were very popular). Clothes like "Igeorgi" and other important clothes known as "Ochéb'ili" were kept in the boxes. To make these clothes retain their sweet fragrances at all time, some ball-like scented materials called "éta" were procured and added into the boxes.More so, it was a thing of pride for the women to adorn their rooms with a collection of plates, bowls, buckets and cutlery neatly packed into "Adudu" a network of locally-weaved net made for such purposes. Some of these items were given by a mother to her newly married daughter as presents.

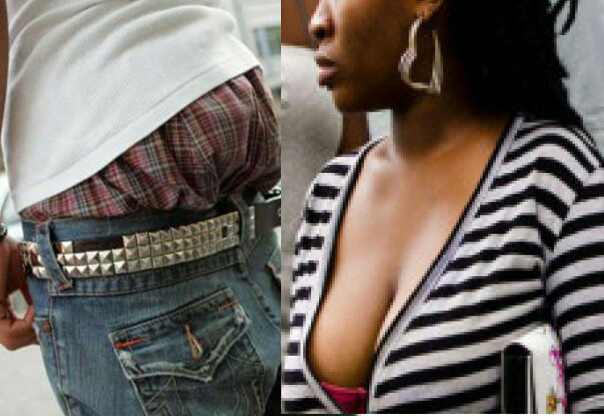

In a similar vein, young girls of my generation prided themselves in dressing decently at all times. In fact, it was a shameful thing for anyone of them to be dressed in anything that dishonestly exposed their priced "treasures" hidden far away along the gorges of their chests and in the troughs of their thighs. Their shirts had no cleavages that exposed their well-reverred breasts. They wore no eye-lashes, no Brazilian-made artificial hairs. They did not need it to look beautiful and sexy. They did not bleach their skins to look like the whites. In fact, the black pigmentations of their skins was a natural attraction only blind eyes could ignore. They favoured African hairstyles made of threads "Éf'owu" and a ridge-like network of hairdos (Éf'abo" or Éyi kabo) that made them more beautiful than our modern girls' hairdos.Their skirts had no openings that offered any free-to-air views for every dick and harry. They demanded no money from any man to be able to buy fanciful clothing and hair materials as they were hard-working folks. They showed great industry by engaging in various lucrative ventures such as farming, garri-processing and sale,collection of banana and plantain leaves for sale,(they were used as wrappers for "Okpa" a local delicacy made from beans (Eje) or bambara nuts (Ikpeyi). They equally hunted and collected local snails ("igbi, akihé, ollo") which they took to the local markets for sale. With the proceeds, they bought soup ingredients for their mothers and bought their personal items. The body creams they used was locally sourced. Only big girls of those days used Vaseline as the rest showed contentment in the use of another type of palm kernel oil known as "An'enyi".They were highly contented with what was available.

In my generation, it was almost a taboo for anyone to mention openly the word "vagina" (or 'utu'in Idoma) or penis "api".In fact, an insult pointing to the respected private part of a woman known as " éch'utu' came with certain sanctions from the women, the "Aanya". The guilty party usually would be forced to kill a hen to appease the women. They could enforce this by group protest with some of the women removing their wrappers as they filed out to the scene of the incidence from the village square or the " Ikpoke" where they would first converge at the sound of a thrilling voice alarm of the victim of such an insult as it rented the serene air,typical of the village,to register their displeasures with the insult.

In those days, young virgins could walk about in the village with their virgin breasts exposing their sexy nipples. Whether they were going to fetch firewoods from the forest or water from the local stream or rivers. In fact, the sight of their breasts as they walked with balanced gaits with their local pots called "Été", buckets called "ikpoji" or basins called "ogbanjé) strategically but skilfully balanced on their heads,was a fascination on its own. Yet their Innocent breasts exposures meant nothing to us, the young boys because of the high level of discipline ingrained in us by our parents. We had no case of rape to contend with. As a matter of fact, a mere sight of their breasts could make us feel like we were in heaven. We could chat about this experience for days as we went hunting (Oté oota) fishing(Uwo oota) and collecting bush mangoes (upi ookpo) as boys.

On our own part, we, the boys,were well dressed. Even when we had no slippers to protect the inlets of our feet from the scorching heat of the sun during summer, we still showed decency in the way we wore the alternative to slippers. It was a flat fruit-shell of a mahogany family tree called " ukpo" while the shell was called " ap'ukpo". We would pierce holes in those shells and put ropes through to come up with a network of straps sometimes with a kaleidoscope of styles. Those were the kinds of sandals we wore as we returned home from the school, market, farm or hunting.

We wore our trousers to cover us from the waist to our ankle levels. We knew nothing about sagging of jeans or pants; we had no boxers to expose from inside of our trousers. Only mad men and women wore sagged and tattered clothes. Even some of them were never naked. Mad men like Ogwuche Eligwu known then as 'Ogwuche Akatakpa', 'Adakole Iwewe' also known as "Adakole Omiyéyé" all in Edumoga knew the value of decent dressing.

Some of our elderly men wore "Opepe", a kind of clothing that covered their waists and their thighs,usually used when they wanted to take fresh air as they laid in their local " ugada" under bush mangoe trees or in the village square "Ikpoke" after a hard day on the farm.

From Oladegbo( my mother's hometown) to Ingle Edumoga,(my own hometown); from Apa/Agatu to Otukpa; from Utonkon to Ochobo; from Igumale to Oju, decency in dressing was a highly enforced cultural value in my generation. In my generation, dressing was worn, not to kill and confuse members of the opposite sex, but to cover nakedness and command respect in a community in an aesthetic style. This is the generation I am proud of.

Culled from "My Generation: My Pride." Unpublished by Ogiri John Ogiri.

Comments